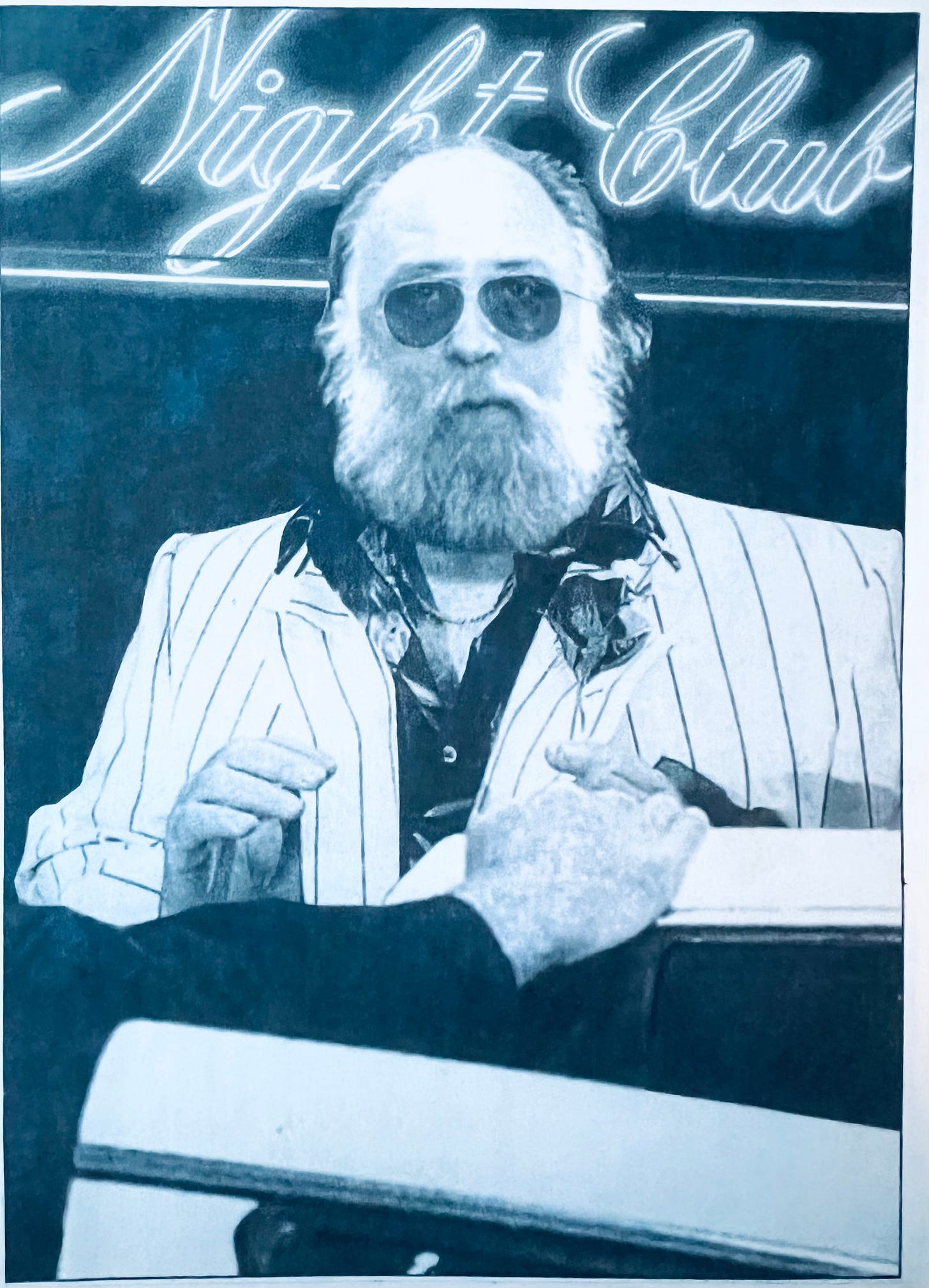

Big Larry was Larry Gaynor. He had an Orson Welles voice, a large beard, and a bikerish fashion sense, with leather featured. He was six foot eight, so naturally he was challenged in bars by shorter men. “The bigger they are, the harder they fall,” they would say to him, puffing out their chests, craning their necks. “Sure, pal,” he would boom down at them. “But the smaller they are, the more often they fall.” His performance of machismo was partly an over-the-top parody, though only partly: if attacked, he’d hit back. He had the fastest mouth in the West and few inhibitions, though he usually offset the cutting edge with an overall kindliness, being an empathetic mushball at heart. He also had a highly functional bullshit detector, having been a professional-grade producer of bullshit himself.

He was born in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, to parents who were, to put it gently, past their optimum reproductive years. His story was that his mother went to the doctor believing she was starting menopause.

“I have wonderful news for you, Mrs. X,” the doctor said.

“That’s Miss X.”

“I have terrible news for you, Miss X.”

According to Larry, his mother was spherical in shape – “Standing up or lying down, you couldn’t tell” – so it was no wonder she hadn’t suspected she was pregnant. “The old bugger,” he said (meaning his father) “knocked her up, so they had to get married.” The aging newly-weds must have been astonished when they found they’d brought forth a precocious giant.

Like a lot of tall kids, Larry was expected to act older than he really was. As a result, he got into trouble early; he learned early, too, how to slide out of it. Graeme used to say you could set Larry down in any city of the world with nothing but a handful of change, and by nightfall he’d have a square meal, plenty to drink, and a place to sleep. Resourcefulness, a quick wit, street wisdom, and low animal cunning: that was his toolkit.

In adolescence he’d tried the military, via the Collège Royal Militaire de St. Jean, situated near Montreal. (This was the same institution Graeme had flunked out of a few years earlier.) While there, Larry honed his ingenuity skills. Taking exception to the demand that he make his bed every morning to strict military standards, he made it perfectly once, then slept on the floor the rest of the time. He rented a small plane and flew bootleg liquor up from New Hampshire, a lucrative enterprise. Then he convinced his fellow students that, instead of working a substance called “whiting” into their parade belts with toothbrushes, they should collectively invest in a big vat of the stuff (with a profit margin for him) and simply dip the belts into it en masse. But this technique didn’t work, so he had to whiten all the belts himself, with a succession of toothbrushes.

The widespread realization that Larry was not officer material occurred during a dress parade, reviewed by several generals. The boys were supposed to sew lead weights inside their pant legs to made them hang evenly over the tops of their gaiters, but Larry didn’t see the point of that. Why not just roll up a couple of hand towels and use those instead? All went well until the marching started and the towels fell out. “What is that?” “It’s a towel, sir.” “Pick it up. I’ll speak to you later.”

Since that time Larry had been many things, including a carnival joint operator, a bouncer, and a fire eater, though he gave up the fire-eating after he set the paper decorations at a children’s birthday party ablaze. He’d lived here and there and done this and that, some of it borderline criminal. But now he’d written a novel. It needed work, so early in the 1970s Big Larry and his novel were flung our way by Dennis Lee at the House of Anansi Press: he thought maybe Graeme and I could do something by way of editing. The novel was a sprawling, over-the-top rigamarole; in the scene I remember most vividly, a large adolescent accidently cuts the testicle off another boy with his skate blade during a hockey game. The book ultimately could not be corralled, despite our best efforts, but Larry became a regular visitor at the farm. Liquor and cigarette smoke went into him, and out came stories. For instance:

Larry had been living in London at the time of his first suicide attempt. According to him, he’d jumped out a window of the Crunchy Frog Studios, intending to drown himself in the Thames. The attempt came to nothing, however: “It was low tide, and there was only a lot of wet mud and old washing machines.”

For his second suicide attempt he’d enlisted Walter, a perennially pot-addled typesetter, to assist him. He, Larry, would stick his head in the oven. Walter would sit on the other side of a curtain so the sight of dying Larry would not distress him and write down Larry’s will as it was dictated from inside the stove.

This scenario commenced: “I, Larry Gaynor, do hereby bequeath … this oven is filthy, doesn’t anyone ever clean it?” After a while it occurred to Walter that he should probably do something to stop Larry from killing himself, so he phoned the Suicide Prevention Hot Line.

“My friend has his head in the gas oven,” he told them.

“Is he still talking?”

“Yes.”

“Well, wait until he stops talking and turn off the gas.”

“Worst thing was,” said Larry, “it wasn’t even the kind of gas that kills you. It just gave me a terrible headache.”

Larry was frequently short of cash; he occasionally supplemented his income by writing romantic nurse novels under a female pseudonym. During one of his lean periods I got a call from my sister-in-law. She and my brother were going on a trip, and the minder hired to look after their three boys had got sick, and they were leaving in just two days. It was an emergency! Did I know anyone?

“How about a six-foot-eight ex-biker, con artist, and fire-eater who writes nurse novels?” I said.

“Does he speak English?”

Ill-advisedly, my sister-in-law gave Larry the number of her poultry provider, Jack the Chicken Man, and told him to buy whatever he liked and put it on her account. When she returned, she found Larry had been ordering two turkeys at a time: one for the kids and anothe for himself. “The bill was a couple of yards long,” she said. “But at least I didn’t have to worry about burglars.”

The boys were twelve, ten, and six and a half, approximately. Larry was highly popular with them. He took them over the speed bumps at fifty miles an hour, he told them whoppers or possibly true stories about his adventurous life, he attended Parent-Teacher Night with one boy sitting on each of his outstretched arms.

“I AM IN LOCO PARENTIS,” he pronounced in round tones to the astonished homeroom teacher. “Have the boys been behaving themselves? If there’s a problem, you can deal with ME!”

Rapid nods! Oh yes! Models of propriety, those boys!

By way of entertainment, Larrry let my nephews read his nurse novel as he was writing it. He also taught them how to swallow forks, sew buttons onto themselves, and butt out a cigarette on a tongue. The parents had a few surprises waiting for them upon their return.

“You’re sitting at the dinner table and your kids start eating the silverware,” said my sister-in-law. “It’s a little unusual.”

*

In the summers Larry would revert to his carnie persona, setting up a “joint” at local fairs and amusement parks. His joint was a ball toss: you were supposed to knock over a crazed-looking doll, which had a fringe of lamb’s fleece all around it to confuse the aim. While working at events near us, he’d stay in a dilapidated trailer that someone else had left at our farm, coming inside to use the bathroom, and also the phone.

One morning I was doing a literary newspaper interview. The reporter was there with his reel-to-reel tape recorder; his photographer was with him. Graeme was away.

The three of us were sitting over our coffee, working through the standard interview ritual, when Larry stalked in. He headed for the phone, which was on the kitchen wall.

“Klara,” he shouted. Klara was his girlfriend, who lived in the city. “Klara! I’ve got crabs!”

The interviewer and the photographer snapped awake. Not only did Graeme have another woman that he was phoning right in front of me, but he also had pubic lice! Why was I being so laid back about this?

“Well, I don’t know,” Larry roared. “I was in the shower, and I looked down at my freckles, and they were MOVING!”

“Want some coffee?” I asked him. Then I noticed the scandalized though titillated expressions of the two newspapermen. “Oh,” I said. “You think this is Graeme! No, this is Larry.”

Even better! I had another man on the string in the absence of my spouse!

Larry scowled at them. “You have a problem?” he said, in his best biker manner. They shrivelled.

How to explain?

Towards the end of the seventies, we spent a year in Edinburgh – Graeme was on a Scottish-Canadian writers’ exchange – and Larry visited us. An editor friend took him to lunch at Henderson’s, a famous vegetarian restaurant specializing in wine and whipped cream.

Henderson’s was below street level: you entered it via a platform and a set of descending stairs.

Larry paused on the platform and surveyed the roomful of virtuous diners below him.

“I … once… weighed… ninety-five… pounds,” he boomed. The audience looked up. He was now two hundred and seventy, give or take.

“And then…” he continued. “And then… I became… A VEGETARIAN!”

Forks dropped. The editor friend cringed. Larry descended the staircase, grinning like a troll.

At that time we had a three-year-old, so we’d joined something called Mums and Tots: sand table, modelling clay, reading corner, games. The mums brought biscuits and made tea. One week I took Larry to Mums and Tots: he’d volunteered. The mums were happy to see him, since toddlers can get a little boring.

What activity would Larry like to supervise? the mums asked.

He chose the reading corner. Surrounded by an eager group of tots and eavesdropped upon by the mums, he dove into the kiddie book on offer, changing the words and plot to suit himself.

“One bright, sunny morning, Little Rabbit Bun-Bun went down to the Dingly Dell and poured himself a big glass of Scotch. Glug glug glug, went Little Rabbit Bun-Bun. Let’s have more!”

Every Mums and Tots ended with us all standing in a circle and acting out a little song. We began by stretching our arms high in the air:

Stand up high as tall as a house,

Crouch down low as small as a mouse,

Then pretend you are a drum,

And beat it like this, a rum-tum-tum.

Gamely, Larry took his place in the circle. “Stand up high as tall as a house...” Up went Larry’s arms, and up went his woolly jumper too, revealing his big hairy tummy. Wordless sensation among the mums.

“Crouch down low as small as a mouse…” Larry did his best. With a rending sound, his pants split right up the back.

For weeks after that, the mums would ask, plaintively, “Where’s your large friend, then? When’s he comin’ back?”

Eventually – after we’d moved off the farm – Larry got a gig with television, doing scripts for a popular serial called Seeing Things that featured a clairvoyant detective. Once in a while he’d make a cameo appearance in it, wearing a leopard skin as a schill for a girly show or casting himself as an underworld heavy. He’d write our names into the dialogue, then phone up after the episode had aired.

“See the show?”

“Yes,” we would say, “and we noticed the mention.”

“Just checking.”

Larry’s talents did not go unnoticed. He wrote for a number of other shows, including The Great Detective and Street Legal. He built up a portfolio, and lived off the fees and residuals. He didn’t become exactly respectable, but he did become solvent.

On his final trip to England, when the emphysema that was to kill him was already gaining ground, Larry encountered a mugger. By that time he was a senior citizen, with greying hair; he must have seemed an easy old-codger mark. “I was in a pub, I went out back to take a leak, and this wanker with a knife comes up and says, ‘Gimme your wallet.’ ‘Sure, pal,’ I said, so I took the wallet out and threw it on the ground. When he bent over to pick it up, I kicked him in the head and took his wallet. I got two hundred quid off him!”

Time passed. Larry moved into PAL, the Performing Arts Lodge in Toronto, which was for retired theatre people. Gradually he got weaker. He had trouble breathing and walking; he needed a wheelchair. The beard had to go because he’d set fire to it with a cigarette while hooked up to his oxygen tank. “I almost blew up my face!” Big joke.

When he was dying, I went to the hospital. (Graeme was away, much to his lasting regret.) I’m not sure why they let me in, but Larry didn’t have any next of kin so maybe they thought I was better than nothing. He was already semi-conscious, but he managed a squeeze of the hand. “It’s okay,” I said. “We’re all here.” This was metaphorically true. “We all love you.” This was not a metaphor. Another squeeze, and then he drifted away.

Before going into hospital, Larry left a message on his voicemail that said: 'I am elsewhere, sliding among the dimensions - leave a note.' Some of his old friends used to phone the number just to hear his voice.

His memorial – held in a pub – was attended by a wide spectrum: people from his London days, from his carnival past, from the radio and film and television worlds. And several old lovers. There was a lot of crying, especially from those he’d helped – much of his residual money from his shows had gone to other people. Those who’d known him when they were children wept especially hard. For them he was magnetic Uncle Larry: part Santa Claus, part enchanted bear, part forest fire, part magician. How could he not be missed?

#

(P.S : Larry was one of the models for Zeb, in my novel MaddAddam.)

He didn't actually put the cigarette out on MY tongue, only on his own tongue.

I can't remember who said it, but the sentiment "when a writer loves you, you can never die" applies here. A beautiful portrait of your friend.