What Is This Health Care, Earthlings? #2: THE TOMMY DOUGLAS TEA TOWEL

Before Tommy Douglas, there was what?

Here is the Tommy Douglas Tea Towel. (Note: Achieve anything public, and sooner or later you will end up on a tea towel. I haven’t quite got there yet, but it’s imminent. Then people dry their dishes on your face. Be careful what you wish for! As for stamps, we won’t go into the whole licking thing, about which many tasteless jokes will be made at your expense.)

Who was Tommy Douglas, why does he rate a tea towel, and why does the tea towel say he was the father of Canadian Medicare? In a nutshell: Tommy instituted Canadian public healthcare first in Saskatchewan, where he was premier, and later pushed it for all of Canada. By then he’d become leader of the CCF (since 1961, the NDP), the third largest political party in Canada. Though it has never formed a federal government, it sometimes holds the balance of power.

Tommy was keen on publicly funded health care because as a boy he almost lost a leg to osteomyelitis. His parents couldn’t afford to pay for advanced treatment, but an expert orthopedic surgeon treated him without charge and saved the leg. As he said later, "I felt that no boy should have to depend either for his leg or his life upon the ability of his parents to raise enough money to bring a first-class surgeon to his bedside.”

We do tend to take things for granted once we have them. But what was it like before public healthcare? Well, my children, I can tell you. I was there.

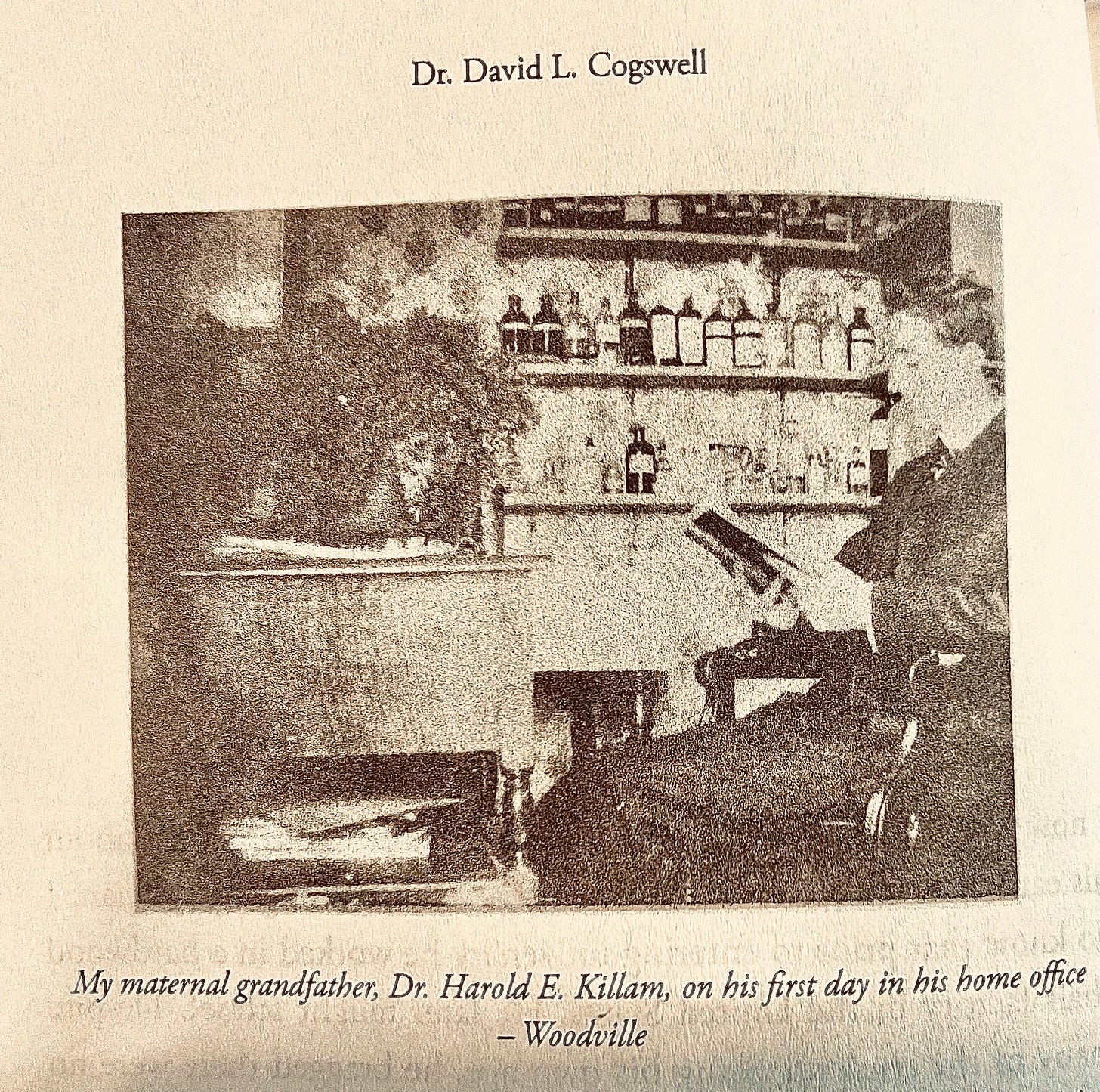

Let’s take the life of my grandfather, a country doctor in Nova Scotia in the first half of the 20th C. His offfice was in his home, as he had no hospital at his disposal. You can see by what’s on the shelf behind him in this picture that he also mixed his own potions and lotions and pills. My mother used to describe people coming to the house with their arms partly cut off (sawmills, axes), or in an advanced state of delerium (various fevers, unknown diseases, and so forth). Her brief comment: “Don’t get sick.” She certainly tried not to get sick, herself.

Babies really were delivered by my grandfather on kitchen tables. There were telephones then — all party lines, people listened in — so you could phone for the doctor, and miracle of miracles, he would come! He made the rounds with a horse and buggy in summer, a cutter in winter. (Hint: a cutter is, or was, a kind of sleigh.) He had a buffalo robe and some heated bricks for warmth. The horse knew its own way home, so he could sleep in the buggy or the cutter.

A lot of his patients were not exactly in the money economy, though they would not have described themselves as “poor.” How did they pay? In wood, chickens, or beans. During the Depression, things got worse. My mother said they certainly got tired of beans. Naturally this doctor was revered: he never refused treat a person because of lack of money.

Here is a picture of him from a book by my cousin, Dr. David Cogswell, who was himself a country doctor in Nova Scotia. His father, Dr. Laverne Cogswell, was a country doctor too. (Bonus in the book below: picture of me, as an early teenager, with my brother and some of my cousins and a home-made boat called the WEDOODIT .. we did go out in this boat on the Bay of Fundy not knowing there was a hurricane warning. They were about to send out Search and Rescue when we reappeared.)

Back to the main plot: I’m told that it’s almost impossible to get a country doctor in Nova Scotia now — or almost anywhere, for that matter. It’s a hard life. You aren’t a specialist. You don’t make piles of money. You’re always on call.

Cut to my early childhood in the 1940s, still before Tommy Douglas. There were hospitals in cities then, and I was born in one, but it was pay per play: the bill had to be settled before they would let mother and baby out. There was only one vaccine available — the smallpox vaccine — and all kids were expected to get the usual childhood diseases: chicken pox, mumps, and measles. And tonsillitis: rare was the child whose decaying tonsils were not yanked out, usually around the age of four or five. Mine were. I had ether, followed by ginger ale and grape juice, a regular treatment for children recovering from the tonsil procedure.

If you were an unlucky child, you got worse diseases: whooping cough, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, diptheria. I had four little cousins who died of diphtheria: it was a big infant killer. So was polio, so dreaded that kids were kept away from public swimming pools in the summers. Oh, and tuberculosis — I forgot that one. And pleurisy. No antibiotics yet, no sulfa drugs, but at least people knew about Germs.

Maybe not such a hot idea to stuff yourself with floor cleaner, but stranger things have been done.

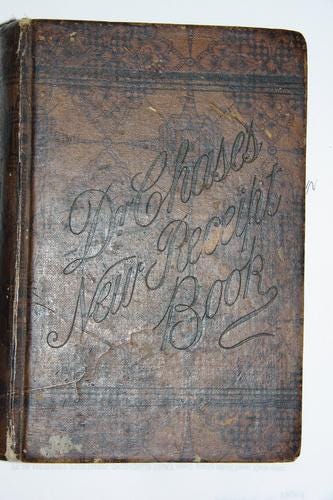

For some of those stranger things, the curious might explore Dr. Chase’s New Receipt Book. (You can get a facsimile, though mine was inherited. If you are writing an historical novel, recommended.) This was a widely deployed household guide in the North America of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries — along the lines of Mrs. Beeton, but with a lot more medical things in it. Yes, there are chapters on Horses, Cattle, Sheep, and Hogs — treatments for their various ailments — and one on Canaries, and under Toilet, instructions for dying your hair with walnut juice (one of my ancestors underlined it— which one, I ponder?), and a rather short chapter on Cookery, but Medical has pride of place.

There’s a dandy pain-killer recipe: I expect it would work very well, as it’s full of opium. As for some of the other recipes and treatments, no need to dye your hair, because it would all be falling out anyway. There’s an interesting remedy for “Menses, To Restore,” which combines ergot with black cohosh and “sitting over the steam of bitter herbs, etc., as the grandmothers knew so well how to do.” Now what do you think that was about? As for cancers of the uterus, cauterize them. Maybe sticking a red-hot poker up yourself was not a very good idea either, but better than nothing, must have been the thought.

Then along came modern remedies, and more vaccines - even one for polio! - and then Tommy Douglas and public health care, and all went merrily forward until it kind of didn’t. What happened? Conditions that were once lumped under vague umbrellas such as “a wasting disease” or “brain fever” were discovered and diagnosed, and treatments for them perfected, and then came transplants, and inserts, and many who once would have died survived to sicken of something else later, and expenses multiplied, and hospitals were built, and clinics, and expenses multiplied again, and people came to expect standards of care that would once have been unheard of.

And governments threw up their hands in the face of the ever-multiplying expenses. All of which were coming out of taxpayers’ pockets, with some grumbling from those who never intend to get ill themselves. Weak to the wall!

How tempting for governments to just underfund the thing until it begins to fall apart, then point to the now-obvious fact that the system isn’t working and default to private clinics. Once you get that snowball rolling it will pick up speed fast enough. Expenses will multiply for the patients, but not for the governments. They will beam and smile and tell you how much of your money they’ve saved. New Tommy Douglases, unable to afford the proper care, will just have to lose their legs.

There’s a boom in alternate health care and online health advice. Scams flourish (though, say the jaded, they would have flourished anyway). I wrote a story awhile ago called “Torching the Dusties” in which angry mobs of young people, faced with a tottering pile of expensive octegenarians, burn down the old folks’ homes with the inhabitants locked inside. It was funny, kind of, then. Not so much now. You can still get a Tommy Douglas tea towel, but where is it now, the glory and the dream? (If you think you’ve heard that before, you have. Five points for spotting it without peeking.)

Meanwhile the best advice is still my mother’s: “Don’t get sick.”

Bonus: A batch of medical-related books:

Some are memoirs + history. (Rob Delany, the Roe book, women doctors.) Vincent Lam and Juliet Wittman are novels. Song of the Cell is science of the future, sort of. All pretty gripping! Some heartbreaking.

My grandfather was also called to the emergency of the Great Halifax Explosion... all doctors available went. Great Uncle Fred flew out a window, still in his bed, and landed safely. Great Aunt Rose fell through the collapsing floor into the cellar. Both survived. He was also an army doctor on call (WW #1.)

Just reading Dr. Chase on the subject of baldness in canaries. They may also be prone to "moping" and "huskiness." And they might get epilepsy, for which you need to cut their "toe nail" until it bleeds. That would certainly startle them!