The French Revvie, Part V: Off With Her Head!

You thought the "Left" was always in favour of the Rights of Women? Not in the French Revvie.

“Off with her head!” shouts the Queen of Hearts in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

But “they never executes nobody, you know,” the cynical Gryphon tells Alice. By 1865, when Alice was published, decapitation was no longer practised in England - they did hanging instead – so Lewis Carroll could make fun of it. Yet only seventy-two years had elapsed since the height of the Terror in 1793: there were still people alive who could remember it. Its impact, and the impact of the Revolution itself, had been immense, and continued to be so during the twentieth century, and —I would argue—into the twenty-first. The disagreements among factions as to the proper form of government are ever-present, and nowhere more so than when “women’s rights” are at issue.

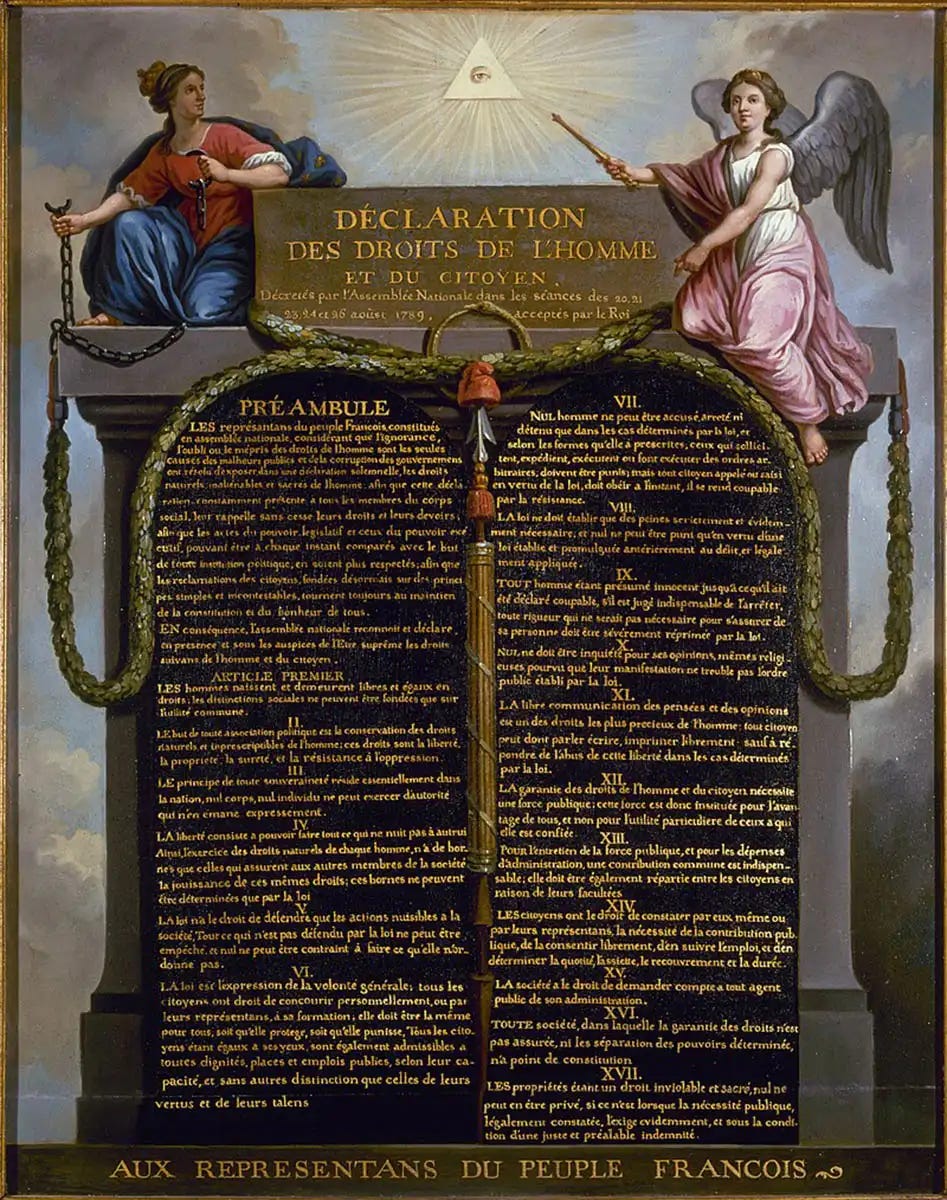

Above is one of the key documents of the Revolution: the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), the very first of its kind. Notice the two allegorical female figures framing it: one is wearing the Revolutionary colours – red, white and blue – and breaking her chains: the French people liberating themselves, no doubt. There’s a sort of crown thing atop her head, which probably meant “the people are now sovereign.” (I’m guessing here. Maybe it’s just a hair style. But it’s a different colour, which means either pin-on bun, weird dye job, or crown.)

On the other side is an angel, pointing with a sceptre to a three-sided triangle (the three Estates – nobility, clergy, and everyone else – all equal), with the eye of Reason beaming forth. This is an adaptation of an earlier Christian symbol which meant, roughly, “the Eye of God is watching you.” A notion terrifying to small children, as many have attested. (The same eye later turns up among the Masons, and thence to the American dollar bill, and thus into my novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, where it is a symbol for the Eyes, the secret police.)

In the middle of the Declaration is a fasces — a bundle of twelve rods tied together (united we stand, divided we fall), with a spear poking out the top surmounted by the Revolutionary red Phrygian cap, a headgear symbolizing freedom, as it was worn by freed slaves in ancient Greece. The fasces had nothing to do with Fascism at that time; it’s a symbol of authority and the law, as it was in ancient Rome, from whence it comes. For more, see: https://www.city-journal.org/article/when-fasces-arent-fascist

This is all very wonderful and idealistic; but the use of female figures in this allegory is deeply ironic, because although Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity were the watchwords, Sorority was not included. It’s the Rights of Man, not the Rights of Men and Women. Although women had been very active in the defining events of the Revolution — the storming of the Bastille, the March on Versailles –

— they were brushed aside when it came down to rights. (Compare the American Revolution, the Russian Revolution (started well for women, at least on paper, but ended badly) and the Chinese one ditto, not to mention “the only position for women in the movement is prone,” thank you supposedly progressive American sixties activists. Now ask yourself what happened to Rosie the Rivetter once her services were no longer required following World War 2.)

In the Revvie, this shut-down-the-women tendency was especially pronounced among the far-left Jacobins led by Robespierre, once they gained power. After all, hadn’t their hero and prophet, Rousseau, pronounced on the gender differences? Women, short on Reason and designed for a subservient role, should stay home, keep out of politics — a man’s job — cultivate their tender emotions, and above all, breast-feed their babies. (This from a guy who forced his housekeeper and the mother of his five infants to deposit all of them in a foundling hospital; not the best way of preserving their lives, IMHO.)

(If you think this Rousseauean two-spheres ideology stopped with the Revolution or was confined to Leftists, think again. Here’s a deep dive into National Socialist sexual dogma, as adopted by Hitler et al: https://historyroom.org/2019/09/22/sexual-policy-in-the-third-reich/ ) And need I remind you of the failure of the United States, home of Liberty, to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, thanks to Phyllis Schlafly?)

Playwright, essayist, and fervent abolitionist Olympe de Gouges (above) took exception to the second-classing of women. She thought the Revolution ought to do as it said: that “Equality” meant, you know, equality — for women as well as for enslaved people; that breaking your chains in favour of Liberty should be more than an allegory; and that women were human beings and deserved better treatment at the hands of the Revolution than the prone role they were being offered. Accordingly, she wrote and published The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (September 1791). You can read about it here: https://revolution.chnm.org/d/293/

De Gouges was very annoying to Robespierre, for several reasons. It wasn’t only that she disagreed with him, though doing this — for anyone – could be damaging to your neck. First, Robespierre worshipped Rousseau, and Olympe was not staying home and breast-feeding. (Also she could write and use Reason: how aggravating!) Second, although a fervent supporter of the Revolution, she was a Girondiste — a member of a more moderate faction opposed to the extremism of the Jacobins. And third, she had the bad judgment to dedicate her Declaration to Marie Antoinette, by this time a much abused woman, although urging her to work for the Revolution.

So, on 17 January, 1793, off came the head of De Gouges. In the statement condemning her, she is called both “impudent” and an “unnatural woman.” There you have it, folks: impudently and unnaturally colour outside the girl lines, and you’re done. Joan of Arc, anyone?

Fat chance of Marie Antoinette working for the Revolution, and even if she had, she was probably doomed. Once the monarchy was abolished, her continuing presence on earth would have encouraged those who wanted it restored. So she had to be liquidated.

This painting of Marie Antoinette being ushered to her death is from a later era — the 1830s —and is by an English painter, William Hamilton. You can tell by the white robe, the spotlight from Heaven, and the piously upturned eyes where the painter’s sympathies lie. Yet the men in the painting are shown not as gloating monsters, but as stern and rational upholders of the law. (Note the sword, often a symbol of justice, in the hand of the man with his back to us.)

The soldiers are holding back a mob, and this mob is pretty interesting to me. Those in it are almost all women. Their expressions are not of anger, but of sadistic glee. They’re getting a kick out of this! Hey, says the painter: maybe Rousseau was right: keep the women out of politics, because they’re unreasonable and prone to excesses. Also they are very into bondage and the humiliation of other women, especially those in the process of being toppled from the heights.

Surely that never happens, you protest! Surely…. (No. Do not say “Taylor Swift being pelted with rotten fruit on the Internet.” Don’t even whisper it. And don’t say “Marjorie Taylor Greene jeering in a bonnet.” Just pretend that women can do no wrong, ever. It’ll take some work.)

I add that the execution of Marie Antoinette was preceded by a barrage of pornography and misogyny that makes the witch-trial treatment of Hilary Clinton look like a fun picnic. This campaign was carried on via posters and pamphlets, many of them illustrated with pictures that showed the Queen of France engaging in various sexual acts, or as part beast, or as a non-breast-feeder with small mammary glands. I will not reproduce any of these images here — this is a family paper — but if you want a deeper dive, try this: https://jamesmccammon.com/2014/04/04/the-empress-has-no-clothes-the-political-pornography-of-marie-antoinette-and-the-french-revolution/

First besmirch and dehumanize, then murder. It’s a well-known pattern.

Here is another iconic allegory that came out of the French Revolution.

This is the famous painting by Delacroix called “Liberty Leading the People” (1830). It’s not directly about the first French Revvie, but about the July Rebellion, which toppled the king, though another took his place for a short time. However, you’ll notice how the themes of the French Revvie repeat themselves. By this time the Liberty figure –chastely clothed in the Declaration of 1789 – has had an adjustment to her dress, reassuring us that she is capable of nourishing the people, as it were. She’s got the red cap and is hoisting the Republican flag. One figure clings infant-like to her feet. Bourgeois and working people both participate. If you squint, you can see a couple of Madame Defarge-like female fighters, but they are very much in the background.

By this time the central figure is known as “Marianne.” Why? I couldn’t find out. One theory is that it was a common plebeian name, and first used derisively by anti-revolutionaries. Here’s another idea: the syllables of the name echo those of Marie Antoinette: Marie-Anne. The Marianne is an anti-Marie-Antoinette (since all symbols exist in pairs, light and dark, positive and negative). Hence the nourishing breasts: Liberty nourishes, monarchies starve.

(Is that a wreath of victory she’s holding, or is it a bagel?)

The female Liberty figure reappears down through the years. The Statue of Liberty, for instance, is a version. The poster for Les Mis — set during the second French Revvie of 1832, which got rid of the monarchy (again) and set up a Republic (again) – has the iconic red, white and blue colours and a suggestion of a cap.

Once more, it uses an allegorical figure that’s female, though it’s a big-eye child version. However, if you look at the barricades and “Tomorrow Comes” set pieces in the film of the musical, it’s pretty much all men.

But the Marianne/Liberty trope persists. There have been a number of Marianne stamps – here are a couple. They keep getting new hairdos, but that waving in the wind hair thing is a constant. Seems Marianne’s hair came down after 1789. (Have I spoken to you yet about the 19th C fixation on women’s hair? If there are enough requests for Victorian hair, I will.)

Yes, females, you can be a potent symbol, and we love you that way. Let your hair loose! Wave that flag, without your top on if possible! But keep it on an allegorical level, please.

That was the story for years. Frenchwomen didn’t get the vote until 1945 and the establishment of the Fifth Republic after World War 2. No wonder Simone de Beauvoir was so crabby: she knew too much history.

So: The French Revvie. A mixed blessing. On the “progressive” end of things, not so good for actual women. But excellent on symbols and slogans that have retained their force over the years, and that have been used — yes — by women. “Liberty,” for instance. Nobody talked about ‘liberty” much before 1789. (But the Philadelphian Liberty Bell, you protest! Sorry, not named that until 1830.) Ever wonder why the Second Wave women’s movement was called “Women’s Liberation”?

And, finally, here’s a treat. It’s the Partisan’s Song of the French Resistance— intensely popular during the German Occupation of France in World War 2 — within which “Liberty” is once more a clarion call. Sung by the opera-singing Stentors (I confess to loving them), who are all men, as are the partisans depicted.

But it was written by a woman.

Behind the paywall there’s a picture of the most notorious naked woman in Art. She caused riots! She too has links to the French Revvie. Yes, it’s a shameless come-on, but what can I do? Anything for bird conservation, which is where the paywall money goes. https://pibo.ca/en/

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In the Writing Burrow to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.