The French Revolution began with jubilation, high ideals, the writing of a Constitution, freedom of the press, the Declaration of the Rights of Man, and hopes for a more equitable future. The once-feared Bastille fell, revealing itself as hollow. The old order had crumbled from within, both ideologically, aesthetically, and especially financially (argues Simon Schama, and who can gainsay?) Working men’s sans-culotte dress — loose trousers instead of knee britches, unpowdered hair, the red Revolutionary cap— became a wise fashion choice. It was time for rebuilding, remaking, replacing, renewing. Everything formerly revered must go! Months and years and days were renamed, to remove the vestiges of the old religion and the monarchy. Time was now to be counted from the first day of January, 1789: Day One of Year One of the sparkling new era.

Then things went pear-shaped, as the Wheel of Fortuna turned. Those formerly sitting on top of it fell off and were crushed. The wheels of the tumbrils carrying people to the guillotine rumbled through the streets. Heads rolled, including that of the King; people cheered.

Then came the September massacres — in 1793, out of control mobs broke into the prisons where priests, aristocrats, and those accused of counter-revolutionary activities were being held, dragged out the prisoners, and slaughtered them by hacking them to pieces. In reaction, and to protect the Revolution from pure chaos — says Sophie Wahnich, author of In Defence of The Terror: Liberty or Death in the French Revolution — the legal mechanisms of the Terror were put in place. By this time the revolutionary bourgeoisie that had kicked off the Revolution were running scared: the bloodthirsty mobs of sans-culottes that they had stirred up to help them in the initial phases of the Revolution needed to be brought under control. So did those from the Provinces who resented having their fates decided in Paris. There was war with France’s neighbours, there was civil war, there were insurrections, there were brutal repressions.

So the lawyers, headed by Robespierre, himself a lawyer, set to work. Most infamous of their concoctions was the Law of 22 Prairial (10 June, 1794), which was supposed to last only until peace with the Revolution’s enemies had been achieved, but in fact — as these things have a habit of doing — began to look more or less permanent. Once this law was in place, it was game on for the Terror. No more freedom of the press. More Terror, and yet more, with Robespierre doing away with anyone who urged a halt to it and calling for yet more purging of traitors and spies and conspirators. (As he had come to identify himself with the Revolution — it was him and he was it – anyone who disagreed with him was, de facto, a traitor.) Complaints were made about the stench of blood – so much of it was flowing, so little being mopped up.

What went wrong?

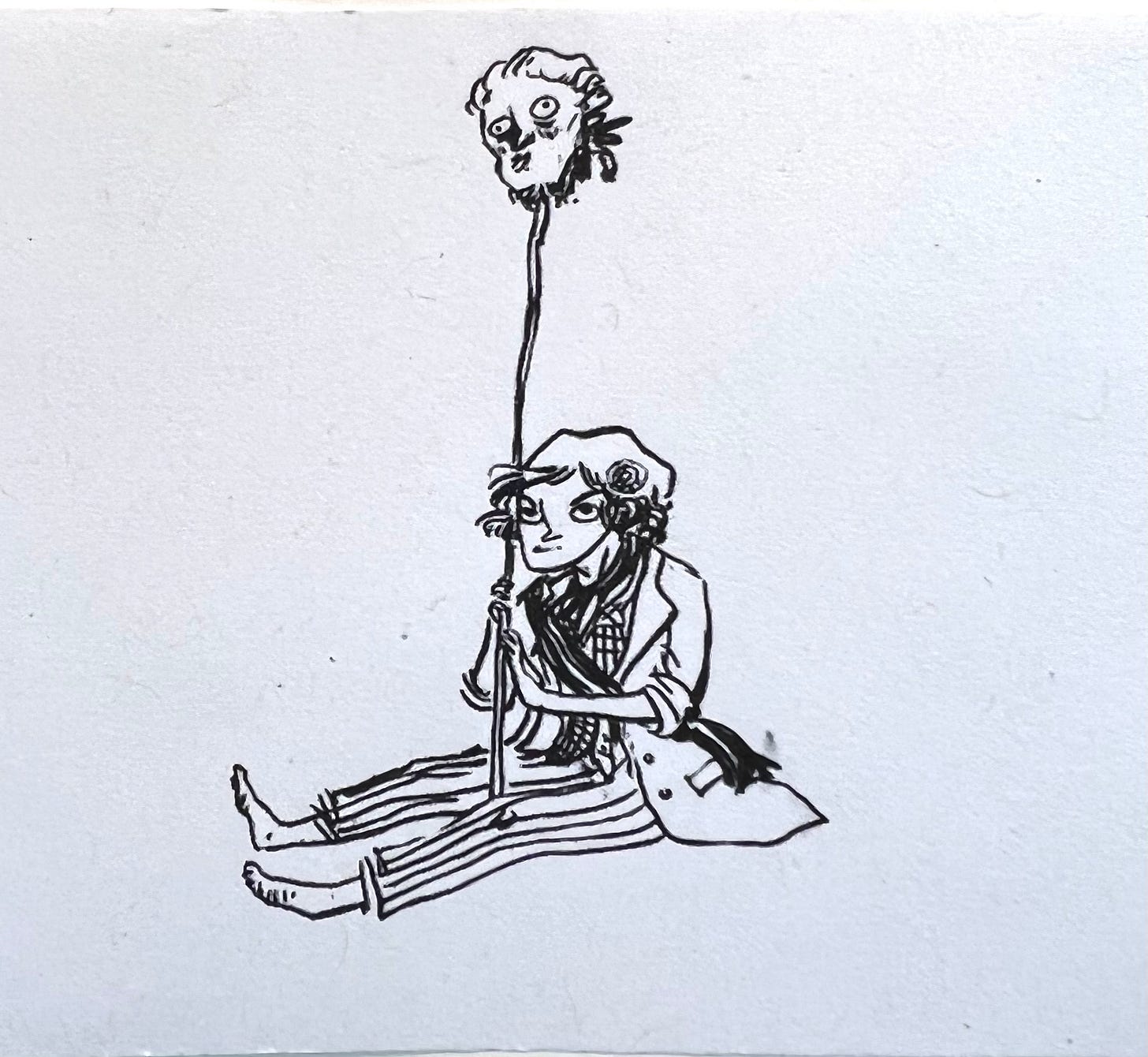

The head of the Princesse de Lamballe carried on a pike.

Before considering this ever-pertinent question — so useful for everything from cake failures to the demise of the Shakers to the onset of the Great War – let’s take a look a a 2019 book about the nature of human nature. It’s called The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution, and it’s by primatologist Richard Wrangham.

Wrangham is far from the first to scratch his head over this question. Why are we so awful, what with cutting off heads and sticking them on pikes? Why are we so good, what with jumping into the ocean to rescue total strangers and dumping money into Save the (Fill in the Blank) for people we will never meet? Or, as Wrangham restates the conundrum in eighteenth-century terms: are human beings fundamentally brutish and violent, and must their evil and predatory natures be restrained by a strong government and the forms of civilization, as Hobbes had argued in the seventeenth century, or are they fundamentally good, and does their bad behaviour stem from their corruption by society, as Rousseau would have it?

We contain the possibilities for both, says Wrangham, who proceeds to explain how we might have got this way. His argument is a bio-evolutionary one, and fascinating it is; but for purposes of the French Revolution, the necessary part is the division between the Hobbseans and the Rousseauists. You will not be surprised to hear that the ideologues of the French Revolution — especially Robespierre — were heavily influenced by Rousseau; but you may be somewhat alarmed by the connection between this optimistic view of our essential human nature and the step-by-step progression to The Terror.

The Law of 22 Prairial is summed up by Ian Davidson in his readable, blow-by-blow 2016 account called The French Revolution: From Enlightenment to Tyranny. It “deprived those who were accused in the Tribunal révolutionnaire of any form of defence: there was to be no interrogation of the accused; no evidence was to be produced against them; they were to have no lawyers; they could call no witnesses; and the tribunal could only choose between two verdicts, acquittal or death, and that based not on evidence but on the moral conviction of the jurors.” In other words, you were guilty if the members of the Tribunal (who were often drunk) felt you were guilty. You were an “enemy of the people”– not the first time this phrase was used (it dates back to Rome), but the first time in the modern era. Certainly it has not been the last.

Why was this law a great idea? For Robespierre, who worshipped Rousseau like a god, it was self-evident: the people were at heart pure, true, sincere, and good, so their feelings were next door to infallible. A Hobbesian would have put in some checks and balances, but Robespierre didn’t think any were needed. (This idiotic stance is joined at the hip with the notion that children never lie about, for instance, Satanic abuse, or that nobody ever lies about, for instance, sex.) If this situation reminds you of modern-day guillotinings via social media – the kind based on rumours and emotions, with no evidence presented – you many be excused.

As for the crimes of which a person could be accused, they were many. Not just deeds and words, but thoughts — and of course the pure, true and good people could tell what the accused was thinking just by looking at them — were to be valid reasons for execution. The inward thoughtcrime sins against God that would once be confessed to a priest morphed into sins against the Republic, but this time there was no clemency, no divine love, no absolution. Sinners were not to be punished or reformed, simply erased. The Constitution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man, and freedom of the press — those worthy items that the Revolution had initially fought for — went out the window.

Then enthusiasm for the Terror began to wane. When everyone is suspected, and on such feeble and fallible grounds, waning of enthisiasm is bound to happen sooner or later. The more people you execute, the larger grows the crowd of resentful relatives and associates; and as some began to fear that Robespierre had a list of those to be eradicated, and that they themselves were on it – for hadn’t he as much as said so? – they plotted to take him down first. The word “tyrant” was whispered, and soon it was being shouted in the Convention itself.

Execution of Robespierre and associates.

This was fatal to Robespierre. In every period there are words that doom you if they are used against you — think of Communist, Nazi, facist, racist, wishy-washy liberal, rapist, heretic and witch – and at that moment, tyrant was just about the worst thing you could be called. It didn’t help that there was some truth to it.

A day later, Robespierre was without a head — condemned by the laws he himself had shoved through. The Thermidorean Reaction, during which the Robespierrists were toppled from power and massacred in their turn, was underway.

Life lesson: Be careful what weapons you devise. Sooner or later they may be used against you.

From French Revolution Comics, in Kate Beaton’s excellent book of graphics, Hark! A Vagrant. Look for it at Drawn and Quarterly, and at peculiar bookstores everywhere.

Next time: I Am Your Vengeance, about Knitting Women, Dicken’s “Vengeance” figure, and repeating patterns of history. Meanwhile, those who would like to know more about why heads on pikes were the gory display of choice in the French Revvie, go to https://www.geriwalton.com/severed-heads-french-revolution/

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In the Writing Burrow to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.