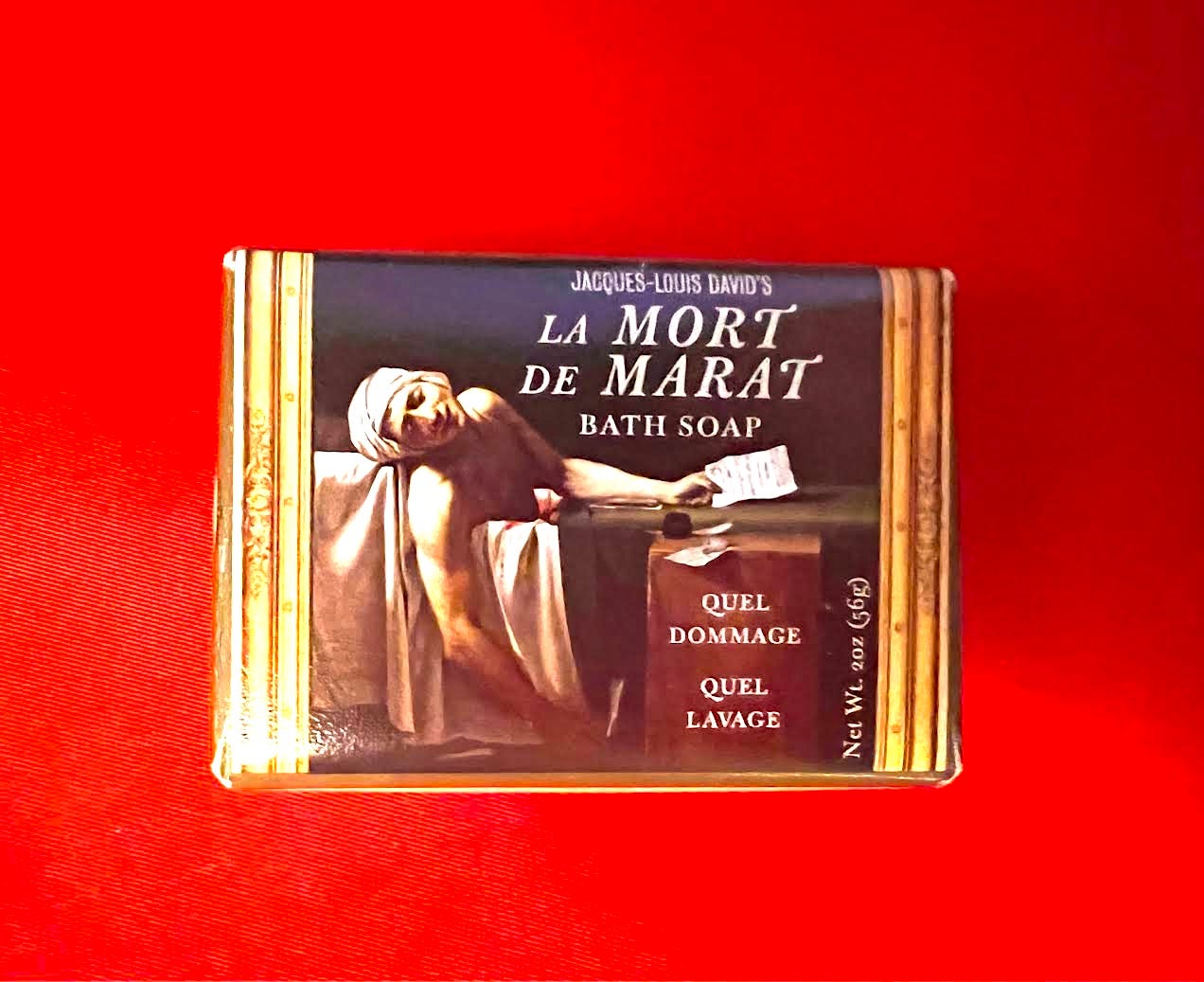

This is Jacques-Louis David’s very famous painting of the Revolutionary pamphleteer Jean-Paul Marat, assassinated in his bath by Charlotte Corday in 1793, and rendered by David in an almost Christ-like and certainly saint-like pose, a good deal handsomer than he really was. Only, in this version, the painting is a bath soap:

(If you want one, they’re available through the Unemployed Philosophers Guild, where you can also get Lady MacBeth’s Hand Soap and Freud’s Wash Fulfillment.)

How did it come to this? “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce,” said Marx: which, in our age of endless consumer goods, we could alter to “First as tragedy, second as kitsch.” Get famous enough and you’re sure to end up as a snow-flurry paperweight, a tea towel, a transforming mug (Robespierre with his head on transforming to the headless version? Just suggesting!), or a singing toilet paper holder. How many people have dressed their dogs up as Handmaids and sent me the pictures, or named their cats Margaret Catwood? Then there’s The Henmaid’s Tale, with an appropriately garbed crocheted chicken. Don’t ask.

Back to the French Revvie. The amount written about this event is truly staggering, and no wonder: it transformed history and our understanding of the relations between the governing and the governed, explored the meaning of democracy and its limitations, and set the rules of engagement — including theories of revolutionary violence and political purges — for over two centuries. “We need the real, nation-wide terror which reinvigorates the country and through which the Great French Revolution achieved glory,” said Lenin. (He got his terror.)

“Revolution” used to mean — at least in the minds of some on the Left — not only the overthrow of the powerful but a levelling of class differences, so that the poor have more and the rich (if still alive) have less. But it’s been used to give a whiff of bolshie cool to just about everything. The Sexual Revolution, the Digital Revolution, the Diet Cola Revolution, the Underarm Deodorant Revolution– you name it, and someone has declared a revolution in it. (See “kitsch,” above.)

However, the derivation of the word – from revolvo, I revolve, I return – points to what usually happens: not a levelling, after which we will all exist in a utopia of equals, but a turning of the wheel. The metaphor of the Wheel of Fortune was well understood in past centuries. Here is a Wheel of Fortune tarot card from the Visconti-Sforza deck of the mid fifteenth century.

In the center of the wheel is the goddess Fortuna, depicted as blind (“blind chance”), who is turning the wheel. At the top is a figure who is saying “I reign,” in the hard-to-see golden voice bubble to the card’s right. This figure, though top of the heap for the moment, is sitting on a platform that looks quite unsteady; also he has donkey ears, probably meaning he is stupid, silly, a jester: jester outfits had donkey ears. To the card’s left a figure is moving up - also with donkey ears — saying “I will reign,” and to the right one is tumbling down, saying “I have reigned.” Underneath the wheel is a poor, tattered old man with no shoes— a peasant or laborer who upholds the wheel on his back and is also being crushed by it. He is saying, “I will never reign.” (I can’t actually make out the writing here, but I’m willing to believe Wikipedia, at least in this instance.)

In this rendering of the revolution of the wheel, there are power struggles among those in the better clothing — each wants or has wanted the top position — but the status of those at the bottom, en masse, doesn’t change. Bsck in the day those would have been land workers — peasants, serfs, agricultural labourers, the enslaved. By the late 18th century there were a lot of poor people living in cities: that’s what allowed for the formation of the Parisian “mob” or sans-culottes that determined so much of the course of the Revolution. As the wheel turned, small-town lawyers (such as Robespierre) rose to the top, and others —such as the King Louis and Marie-Antoinette – fell off.

Soon the fallers-off included Robespierre’s old pals, Danton and Camille Desmoulins, as factionalism and power-struggles accelerated and those on the Jacobin “left” pushed one another into more and more extreme positions, leading to the Reign of Terror. (I say “left” in quotation marks because there was much in the Jacobion stance that leftists of today would not agree with, including the fiat that women’s place was only in the home, breast-feeding like all-get-out.)

And then, quicker than you could say Donkey’s Ears, off came Robespierre’s head, under a law that he himself had pushed through: the infamous 22 Prairial.

Next time (or soon, anyway): The Law of 22 Prairial, the Terror, and how some folks are pushing the equivalent today, and then — next time after next time: How MAGA is analogous to the French Revvie — there can be Revvies on the Right as well as the Left — and, in the event of their revolutiinary win, whose heads are likely to come off. The Vengeance of Trump! Wait for it! Actually, prevent it. It won’t fun, unless you’re a sadist.

Until the next thrilling installment.

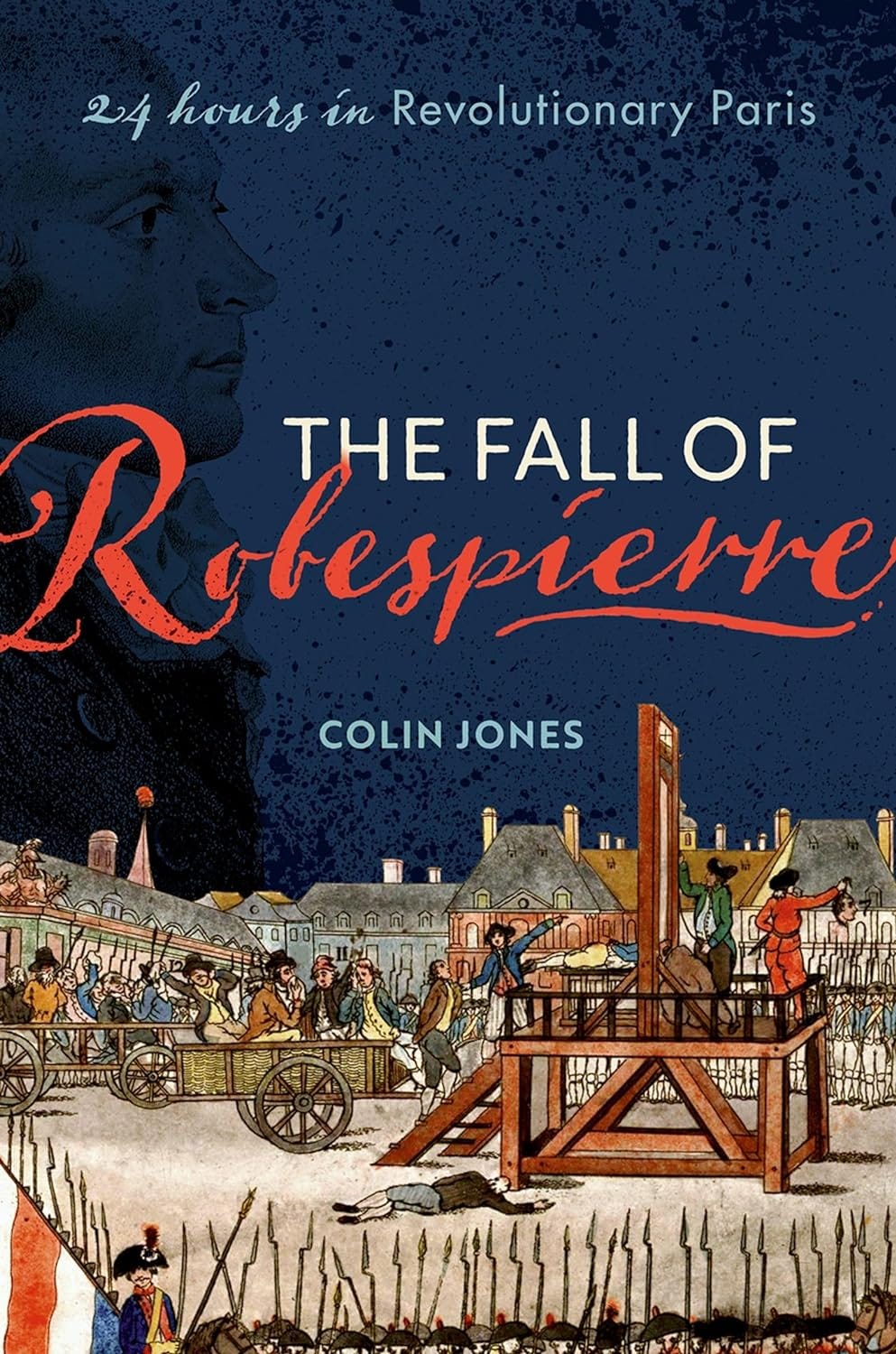

Meanwhile, some books for you:

Very gripping! 24 hours in Paris, at the beginning of which Robespierre had a head and at the end of which he didn’t. Sometimes the wheel spins very quickly! At the end: What was lost as the Revolution dissolved into grudge fights? Many ideals. But some at least have lived on.

This is an all-in account of events, from aristos who just wanted liberal improvemnets to Thermadorians out for vengeance. And look at those angelic revolutionaries! Innocent as children! What are they carrying? The Bastille. As one does. At the end, Schama does a reprise: How much actually changed in daily life for the underclass? Not that much.

This is a side we don’t often hear. Includes how awful things were. Thoroughly documented, but concise and short. Look how much the figure in white resembles the man under the wheel in the Tarot card, or am I hallucinating? Don’t answer that.

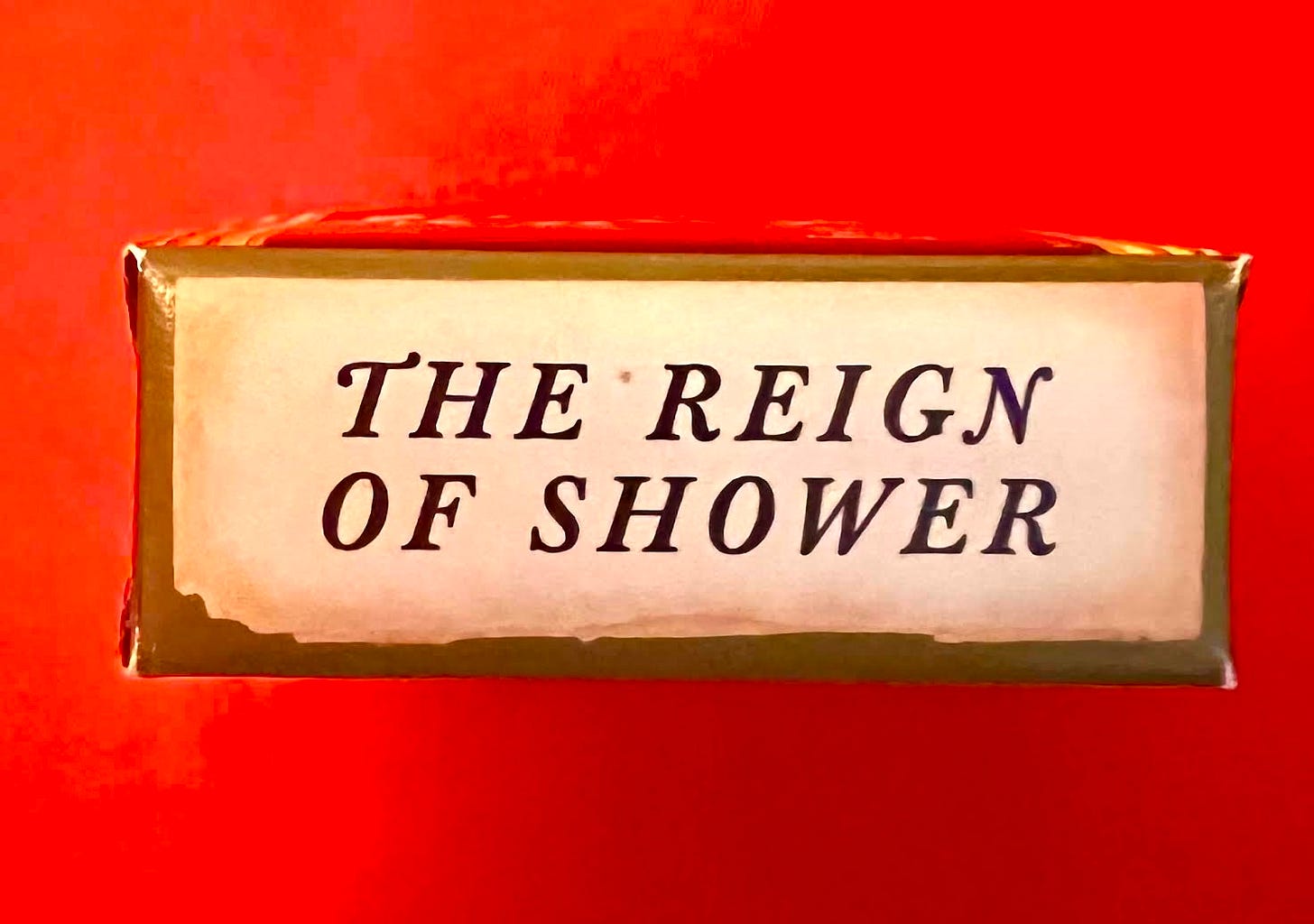

To conclude, here’s my final piece of kitch for you. A sidebat from the Marat bath soap. Sorry, I can’t resist. Own worst enemy, etc.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In the Writing Burrow to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.